16 October 1754 James Finney was now living in Culpeper County and

by this date had bought another 126 acre tract of “unappropriated” or unclaimed

land that adjoined his original grant (Appendix 14). He now owned two tracts of land in southern

Culpeper County, Virginia totaling 326 acres.[i] This area was made up of rolling hills,

bordered to the west by the Blue Ridge Mountains. Once known as the frontier or the western

country, Culpeper County was at this time growing in population. A major goal in a man’s life was to be able

to leave his children land after his death, not to mention to have his children

raise their families nearby. By the

middle of the eighteenth century, most of the land on the eastern Virginia

Piedmont had been claimed and bought, most often by large plantation holders. Little

opportunity existed to expand one’s land possessions so many farmers migrated

west where land was more plentiful.

Certainly James Finney had visited Culpeper County in the years before

his move to improve his land and prepare for his family’s relocation. James Finney may have come in contact with

young George Washington, who had been the Culpeper County surveyor from 1749 to

1751.

holdings (red)

1754 Both New France (in Canada to the north) and New

England wanted to expand their territories with respect to fur trading and

other pursuits that matched their economic interests. Using trading posts and

forts, both the British and the French claimed the vast territory between the

Appalachian Mountains and the Mississippi River. George Washington, now a

21-year-old major in the Virginia militia, was sent to negotiate boundaries

with the French, who were unwilling to give up their forts. Washington led a

group of colonial Virginian troops to confront the French at Fort Duquesne

(present day Pittsburgh). After a skirmish in which a French Officer was

killed, the French forced Washington and his men to retreat. Meanwhile, the Albany Congress was taking

place in Britain as a means to discuss further action against the French. And so, beginning of the French and Indian

War in North America had begun. (See Appendix 15 for known Finney men that

served in this war)

21 August 1755

James Finney witnessed a deed between his neighbor Seth Thurston and Richard

Wayt for 200 acres, which was located on the branches of Maple Run.[ii] This land was on the south border of James

Finney’s land and where Seth Thurston lived and planted tobacco. Richard Wayt, born in Middlesex County in 1708,

had migrated to Culpeper County about 1754 and would take over this plantation while

raising his own family.

1756 War was

officially declared this year by England though it was already ablaze in North

America. In order to secure the rights

to the large western territory in North America, both European powers took

advantage of Native American tribes to protect their territories and to keep each

other from growing too strong, though most tribes primarily sided with and

fought alongside the French.

1757 James

Finney more than doubled his current land by purchasing 476 acres from Thomas Rucker

(see Appendix 16). The land had been

originally purchased from the state of Virginia by Thomas Rucker with a warrant

on 28 October 1756. This large tract of

land was bordering James Finney’s two additional tracts of land to the

northwest and was described as “…near a place called Prickly Pear Rock, Beautiful

Run, on road leading to Caves Foard…”[iii]

20 September 1759 Once again James Finney witnessed a land deed. This time the deed was between Benjamin Head,

of Orange County, and Julius Christy, who already owned land just south of

James Finney, on the Rapidan River.

Julius Christy, a joiner (a form of carpentry) by profession, purchased

the 200-acre tract for 40 pounds.[iv]

8 September 1760 The French and Indian War ended in North American after a treaty

secured Montreal and sent French troops back to France. The war would continue in Europe, where it

was actually known by a different name, the Seven Year’s War (1756 – 1763). Though no members of the James Finney family

participated during the war, several other Finneys were active during the

hostilities (Appendix 15).

25 June 1761

Thomas Crosthwaite, a Culpeper County resident and neighbor of James Finney,

had recently died and his estate had gone to public auction. James Finney bought goods from the estate

along with many other Culpeper citizens known neighbors of James Finney. [v]

1763 James and Elizabeth

Finney’s family had grown. They now had

at least five children. In addition to

John and James, there was Mary, who was the oldest girl, now about five to ten

years old. Two younger children in the

house were William, about three to eight years old, and Elizabeth, who was

probably under five.[vi]

Looking at the English naming

pattern for boys, a third son would be named after the father. Since a child had already received the name

James, then logically this son would have assumed the name that would have been

given to the fourth son, the name of the father’s oldest brother. James Finney’s oldest full blooded brother

was named William; therefore the son received the name William Finney.

The Finney plantation now

consisted of 802 acres, including “houses, orchards, gardens, fences, woods,

water and watercourse”.[vii] There was a country road near the plantation

that was their key to the outside world.[viii] Many travelers and neighbors would pass. Some would be invited to stay if they needed

a place to rest. It was from these

people that the Finney’s learned of the latest news in their area, colony, and

the world.

The house on the farm, located specifically on the

original 200 acre grant[ix],

was probably a modest log cabin. The

home was built with the help of neighbors and relatives. The building assembly used logs for the walls

that were squared and carefully notched at the ends so they would lay closer

together, leaving only narrow cracks to be chinked. Most farmhouses were built with two rooms

downstairs and two upstairs. One of the

downstairs rooms was the kitchen and the other was a bedroom, certainly for

James and Elizabeth Finney. In the adult

bedroom were their feather bed, a small desk, a trunk for clothing, and a

spinning wheel.[x] In the middle of the two downstairs rooms was

a large chimney to warm the house and from which to cook. A ladder or stairway beside the chimney led

upstairs to bedrooms for the children.

There were two feather beds in the boy’s room and one in the girl’s

room.[xi]

The kitchen area was the most active

area in their home. This room also

served as their dining room and living room.

Elizabeth Finney used pewter basins at the sink to hold water, which was

brought in from the well outside. She

also had cooking utensils here; iron ladles, pots and pot rack, a brass kettle,

earthenware jugs, pint mugs, chamber pots and slop bowl, two frying pans, iron

spoons, forks and knives, pewter dishes and pewter plates.[xii] The dining room table could hold as many as

eight chairs.[xiii]

kitchen (below)

In the house, the Finney girls helped

their mother make clothing for the family.

Wool and cotton were cleaned and washed, and then carded. They owned a pair of cotton cards and wool

cards, which they used to fluff the wool and cotton into short lengths or

slivers.[xiv] After the wool was carded, it was spun on the

large spinning wheel[xv]

which prepared it for being woven.

Elizabeth Finney used the woven wool and cotton to make most of the

clothing for her family.

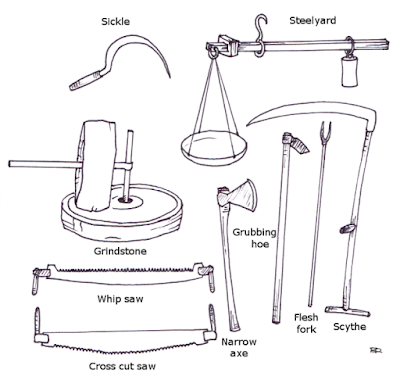

Surrounding the house were other

structures. There would have been a

southern barn for curing tobacco, and a northern barn for storing hay and straw. Animals were often kept in the northern barn

to protect them from harsh weather.

James Finney kept his farming utensils and supplies there also. Among his supplies were sickles, a

grindstone, a steelyard, scythes, a whipsaw and crosscut saw, narrow axes,

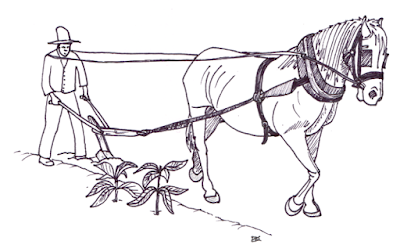

grubbing hoes, a flesh fork, men’s saddles, a woman’s saddle, and bridles.[xvi] He kept a plow in one of the barns that was

used in the fields, and he had a cart in one also, probably two-wheeled, that

was used for hauling and transportation.[xvii] For the cart he, of course, had a pair of

harnesses.[xviii] There was also a smokehouse that was used to

preserve and store meat. Set away from

the house were the Negro quarters, which consisted of one or two small houses.[xix] And, without question, the outhouse was nearby.

Assorted

farm implements located in the Finney barn (above)

and a two-wheeled cart (below)

and a two-wheeled cart (below)

The Finneys owned a small number

of slaves. In the early 1760’s, five slaves, or Negroes as they were most

commonly known, lived on the Finney farm.

There were two men, Jack and Sanckony, two women, Frank and Cate, and a

child named Easter.[xx] The slaves did a majority of the labor work on

the farm. They also assisted Elizabeth

Finney and her daughters with much of the household duties.

The Finneys grew tobacco on their

land and used it as a main source of income.[xxi] Tobacco preparation was not an easy

process. The slaves helped both plant

and pick the tobacco from the fields.

After the tobacco was picked, it was put in the tobacco barn for drying,

inspecting and baling. When the tobacco

was ready, it was taken by their cart to be sold either in town or back

east. They would also use it to trade

for goods from a nearby town storekeeper.

Other important necessities were grown on the Finney farm. They had gardens close to the house that

would yield important vegetables for the family, such as peas, beans,

cucumbers, squash and muskmelons (cantaloupes). Beyond the gardens lay the

hayfields. The hay was cut from the field using scythes.[xxii] This provided feed for the livestock. There was also cotton that would be picked

and cleaned, eventually made into clothing for their family[xxiii],

and fields of grain as well.

tobacco fields

A still was another vital feature

on the plantation.[xxiv]

Fruit from the Finney orchard was used in the still to make brandy and

whiskey. Apples, pears, peaches and

plums were among the fruits grown in their orchard.[xxv] After the fruit ripened, it was picked and

pressed to make cider, then in due time distilled into brandy. They made apple brandy, peach brandy, plum

brandy and whiskey.[xxvi] The brandy and whisky was placed in barrels

or containers to ferment. James Finney stored

vast amounts of brandy via this process.[xxvii] The town storekeeper would take brandy as

payment for anything that was sold in his store. James Finney’s sons, John and James, would

help their father at the still and became very knowledgeable of the trade.[xxviii]

The

plantation had many kinds of animals, used for different purposes. James Finney owned about five horses[xxix],

which were used for farm work and as their main source of transportation. About 15 to 20 cattle were kept in the fields[xxx],

providing the family with meat, milk, butter, and cheese. Other sources of food on the farm were hogs

and geese. There were about 25 hogs

that provided them with meat and about 20 geese that would supply eggs and

feathers (for stuffing pillows and beds).[xxxi] Finally, a few sheep (no more than 10 or 12)

provided wool for clothing.[xxxii] The fences around the farm and fields were

used to contain the animals. They were

either made of stone or wood. Farmers

were constantly clearing glacial stones from their fields in this part of

Virginia and used them for the stone fences.

Wooden fences were made of split logs, 12 to 14 feet long. Most animals, even geese, wore yokes around

their necks to keep them from getting through the wooden fences. Sometimes, farmers would have both stone and

wooden fences.

The

family was probably a member of the middle class and lived quite

comfortably. They owned a Dutch Oven,

which many families did not have at this time.[xxxiii] Also in the house were two washing tubs,

pretty rare for most families.[xxxiv] James Finney had his own carpentry tools and

shoemaking tools.[xxxv] He also had cooper’s tools, which he used to

make wet barrels (storing cider, whiskey, brandy, brine and vinegar) and dry

barrels (storing grain, meal and fruit).[xxxvi] The young John and James Finney learned to

use these tools by observing their father and the slaves.

Working was not the only thing

that the Finneys thought about. At certain times during the year, when there

was not as much farm work to be done, the children were taught to read and

write. James Finney, and possibly his

wife Elizabeth, did the majority of the teaching at home. There was a small

library of books in the house,[xxxvii]

certainly including a Bible, Almanac, and hymnal. Often, the children were read

to under candlelight before bedtime. There were surely times when the children

received additional schooling from a schoolmaster. Schools in the country were built by the

surrounding community who employed the best teacher they could find, requiring

the parents of each pupil to pay a small sum for maintenance. The Finney children would have walked to

school if it were less than three miles and if farther they would ride a

horse. They most certainly felt the

sting of the hickory rod as they daydreamed about free time on the nearby

creeks and rivers rather than concentrating on spelling and arithmetic.

There were

no large towns in the immediate vicinity of the Finney farm. The Finneys would visit some of the smaller

communities that had sprung up around nearby mills. James Finney had to take his crops to the

mill to be ground. Stone ground corn

meal was produced by mounting two circular stones centimeters apart, the bottom

one is ridged and the one on top is rotated by a water powered wheel. Corn was

fed into the center of the stones, ground, caught, cooled, bagged, and hand

tied. Besides the mill, other businesses

could be found in small communities or towns.

These included the blacksmith, the cobbler, the silversmith, the

“pewterer”, the tinsmith, the tanner, the tailor, and a town crier who spoke

out to local citizens about important announcements from the colony. The merchant, who ran the general store,

traded and sold almost anything to the colonists. These goods included food items, farm tools

and supplies, cloth and clothing, books, kitchen ware, and many other supplies

needed on the farm.

As mentioned before, the Finneys

used country pay, country money, or natural commodities, which included

tobacco, alcohol, rice, wheat, and maize, to pay for goods. Currency and coin were also used and based on

the British pound, shilling, and pence.

Due to the scarcity of the official British coins, colonists used coins

from many other countries, but typically the Spanish and Portuguese milled

dollar. However many forms of payment

existed, the conversion to the British pound, shilling, and pence was

commonplace.

Rappahannock River

where sailing vessels are offloading

supplies at the wharves

Further away from the Finney farm

were larger towns that would offer both necessities and excitement in new

forms. Culpeper citizens were very familiar with Fredericksburg, Virginia, the

closest market to sell goods.

Fredericksburg was about 50 miles to the east and was situated on the

Rappahannock River. Ocean going ships

anchored in the river and discharged incoming arrivals and goods from Europe,

the Indies, and other American colonies.

Exporters refilled the ships with the goods produced locally to be sent

to foreign destinations. For the young

Finney boys who often accompanied their father, large towns like Fredericksburg

meant fairs to attend, horse races, cockfights, and wrestling matches. Other towns nearby included Orange 12 miles

southwest, newly created Fairfax (later known as Culpeper) 20 miles northeast,

Charlottesville 25 miles southwest, Staunton 60 miles southwest, and Winchester

75 miles northwest over the Blue Ridge Mountains.

A Germanna settlement made its

home near the mouth of White Oak Run in 1725.

This location was about eight or nine miles to the north of the Finney

farm, in the general direction of Fairfax (later Culpeper). The German settlers built Smith Island Fort,

a small fort and stockade, and in about 1740 built the Hebron Lutheran Church,

which remains standing today. The White

Oak Run was originally known as Smith’s Run and though it is now gone, there

was once an island at the convergence of the Smith’s Run and another branch,

hence the name Smith Island fort. German

families settled all around the area and lived very close to the Finney family

to the immediate north.

10 February 1763 A treaty between France and

Great Britain was finally realized and the Seven Years War in Europe was

over. As a result of the treaty, James

Finney, and most Virginians, soon became outraged when Great Britain issued the

Proclamation of 1763 prohibiting the American colonists from settling west of

the Appalachian Mountains. This would halt westward expansion of the colonies,

limit land, and ensure that Indian raids would continue from the west. These problems would have a great impact on

the Finney family since they lived near the Proclamation line, immediately east

of the Appalachian Mountains.

Before the Proclamation of 1763,

Virginians had grown bold, migrating west over the Appalachian and Blue Ridge

Mountains. This movement had meant that

Culpeper County had become less well-known as the west or the frontier. But now, the settlers in the new western

frontier had to move back over the mountains.

Many of these settlers returning would stay in the foothills of the Blue

Ridge Mountains, quickly increasing the Culpeper County population. Culpeper County and the area nearby, during

this era, was often called the middle ground between the cultured east and the

untamed west.

21 April 1763

James Finney was at the Culpeper County Court meeting in Fairfax petitioning to

modify or “turn” the road at his plantation.

The Court ordered Elliot Bohannon, William Rice, and William Walker to

be sworn before a Justice of the Peace and then to travel to James Finney’s

plantation before the next month’s court meeting to study the requested road

modification and then report to the court the convenience or inconvenience to

residents.[xxxviii] A road modification would have been requested

for many reasons, such as to provide the Finney family with a more convenient

route to the mill, town, or church. New

mills, towns, and churches were springing up as the area became more populated

and since there remained few roads in Culpeper County, a new church built just

a mile distant, may call for many miles of travel by road.

The main roads in southern Culpeper County during the

1760s and the approximate location of the Buford (A), Quinn (B), Gibbs (C),

Rice (D), Bohannon (E), and Walker (F) families

19 May 1763 Elliot Bohannon, William Rice, and William Walker

reported to the Culpeper County Court on James Finney’s petition to turn the

road at his plantation. William Kirtley

appeared in court to object to this petition and after all sides were heard,

the court ordered “… that the new way be continued till next fall and that then

the old way be established.”[xxxix] A citizen may object if a new route would

bring less traffic to that person’s home or business, such as a mill.

The young Finney boys could often

be found upon the branches of Maple Run and Beautiful Creek, swimming and

fishing. Children in colonial times were

always searching for adventure and fun after being relieved of their duties

planting and harvesting. The Finney boys

would seek out neighbors to fool around with, such as the Buford boys[xl]

who lived just north of the Finney farm and the Quinn and Gibbs boys just to

the south on the Rapidan River. They

would invariably find themselves involved in games and contests of strength to

display their skills, athletic abilities, and endurance.

Like most other families, the

Finney family was a religious one. They

were probably Episcopalian, as were many of their neighbors.[xli] They lived in Bromfield Parish, which

governed the religious bodies in Culpeper County and some other surrounding

areas. The closest known “established”

Episcopalian church in proximity to the Finney farm was the South Church, or

Vawter’s Church, located about 6 miles to the northwest off the Great Mountain

Road. All persons within each parish

were required to attend the parish church or else pay a fine. Part of the purpose for the required

attendance was to pay the parish taxes levied on everyone within each

parish. In country areas like Culpeper

County in the 1760’s, some parishioners lived a great distance from the

church. For these people, provisions

were made to relieve them from making the long trek to attend the church. “A House of Ease”, similar to a branch

church, was built so people in the parish could attend more easily. At other times, the people of this area just

met to pray with an evangelical neighbor leading the service.

About 1763 Though the Finney

boys were still early adolescents, colonial boys were prepared for their adult

lives at an early age. Boys in middle

and upper class families were sent away from home to train as apprentices in a

trade selected by their father. Often, a

son would be sent to a relative that could offer that training, whatever it may

be. While it was desirable to have a son

learn a new trade, a farmer would prepare his remaining son(s) himself to

operate a farm. Since John Finney was a

teen now, he was likely sent away to learn a trade. Son James, it would seem from future

endeavors, would learn to keep the farm.[xlii]

Summer 1764 Since earlier in

1764 or maybe before, James Finney the elder had not been physically well. He wrote his will on 18 February 1764 stating

that he was “…in an ill state of health but having free and perfect sense of

mind and memory thanks be given to Almighty God for the same and calling to

mind the frailty of all mankind and that there is a time for all mankind to die”

(Appendix 17).[xliii] James Finney left most of his personal assets

and property to his wife and children while two other men were honored with

gifts of land. His “well-beloved

brother-in-law Henry Turner,” his wife’s brother, and his “much respected

friend Thomas Buford” were each promised a tract of land. If his wife Elizabeth died while his children

were still minors, the “respected friend Julius Christy” was to become their

guardian.

June/July 1764 James Finney

died at his home in Culpeper County, Virginia at the age of about 56.[xliv] His death dramatically changed life at the

Finney home. The young John and James were

left to run the farm at a very young age. New responsibilities for these

adolescents would include control over the crops, caring for the livestock, and

helping their mother raise the younger siblings. Without the experienced male figure running

the farm, they relied for a time on the slaves they owned and from family and

friends living close by.

16 August 1764 The last will

and testament of James Finney was “exhibited” to the Culpeper County, Virginia

court by Elizabeth Finney.[xlv] Elizabeth Finney, now widowed and perhaps

about 40 years of age, would act as the executrix, appointed by her husband in

his will written back in February.

Appearing in court with Elizabeth Finney were her neighbors John Buford

and Zacharias Gibbs.

death

of James Finney in 1764

6 October 1764 Elizabeth

Finney appeared at Culpeper County court to present the “true and perfect

inventory of goods and chattels of the James Finney estate.”[xlvi]

James Finney had declared in his will that “none of (his) estate either real of

personal shall be either appraised or sold at public venue” and therefore no

appraisal or sale was made. Elizabeth

Finney returned to court five months later on 21 March 1765 to record

additional inventory of James Finney’s “goods and chattels.” (Appendix 18)

1765 After the death of

James Finney in 1764, Britain continued to harass and bully the American

colonists. Between 1765 and 1770, King

George III and the British Parliament passed several laws against the colonists

and tried to impose very large taxes to pay for their war debts. By reading the Virginia Gazette and talking

with others, Elizabeth Finney taught her children to read while fuming about

“taxation without representation”.

Outraged, many colonial states, including Virginia, met to protest.

Who was James Finnie of Fredericksburg?[xlvii]

There was another James “Finnie” in the Culpeper County area that has resulted

in confusion with our James Finney of Culpeper County. Not much is known about the James Finnie that

lived in Fredericksburg, Spotsylvania County, Virginia. He was first identified as the husband of Ann

Lynn about 1758. She was the daughter of

Dr. William Lynn of Fredericksburg, who was most famed as the doctor of George

Washington, and the widow of John Dent.

Finnie and Dent were married in 1757 or 1758 and received land around

the same time from the will of Dr. Lynn.[xlviii] This land was located just northeast of James

Finney in Culpeper County on Dark Run.

James and Ann Finnie sold a Fredericksburg town lot in 1766[xlix]

and were listed in a Culpeper County deed in 1768 as “of Culpeper County.”[l] A land deed in 1780 for 600 acres on a tract between

White Oak Run and the Dark Run stated that James Finnie had formerly lived

there.[li] Nothing was found for James or Ann Finnie

after 1769, leaving great confusion about who this man was.

James

Finnie of Fredericksburg owned a 425-acre tract

of land on a branch of Dark

Run, received from his

father-in-law Dr. William Lynn’s will probated in 1758

Young John and James Finney

became teenagers in the mid-1760s and were becoming more interested in their

colony’s problems with Great Britain. James

was pretty much running the Finney estate at the time while John may have begun

to ply a trade, which meant that the issues of Great Britain were becoming more

important and meaningful to them personally.

By 1768, the brothers were

members of a county militia. Every able

male over the age of 16 was obligated to serve in his county’s militia, a

requirement that went back into early colonial times and well after the

Revolution. John and James Finney were of age and were expected to train and

serve their county. They served in the

militia under the banner of the Royal Colony of Virginia at this time. There are no records to show this service but

it was the normal activity.

Circa 1771 By 1881, John

Finney appears to have left Culpeper County and moved west. Living in the Virginia “east” was comfortable

and tame while life in the “west” was synonymous with danger and risk. Land was more readily available in the

western portions of Virginia; over the Blue Ridge Mountains. Cheap land could be had in these uncivilized

locations and many colonists took advantage.

However, men were not driven by land alone. Like their recent ancestors before them,

colonial men had an insatiable appetite for adventure and harbored a burning

desire to create a better life for themselves.

Though the Finneys were able to live comfortably in Culpeper County,

John Finney apparently was driven to move west.

Whether following family or friends, or having already spent time there during

or after his apprenticeship, Finney was not living in Culpeper County.[lii]

See Appendix 19 for a review of John Finney’s movements in the 1770s and 1780s.

John

Finney moved to western Virginia, which was made up of

three counties in 1772:

Augusta, Botetourt, and Fincastle.

Evidence points to Botetourt County as his probable destination

1772 The first word of

secession from Britain was threatened in Boston, just before the Boston Tea

Party. The British then flexed their

muscles and closed the port of Boston. John Murray, also known as Lord Dunmore,

was the British appointed Governor of Virginia.

In response to the succession threats, he closed the Virginia House of

Burgesses, which included the colonial representatives of Virginia. These representatives, along with other

legislatures in the state, began to meet in secret committees to discuss these

big problems.

With James Finney now deceased, the story follows his two sons John and

James, with much of the emphasis on James.

Beginning with Chapter 4 and to avoid confusion with the elder James

Finney, the younger James Finney, born in 1752, will now be known simply as

James Finney and John Finney, born about 1750, will be John Finney.

[i] These

two tracts included the 1735 grant of 400 acres of which James Finney Sr. received

half (Orange Co VA Grant Records Deed Bk 15 No 494 LDS film 0029310), and the

grant he bought about 1754 for 126 acres (Culpeper Co VA Land Grants p 611).

[ii]

(Culpeper Co VA Deeds Vol 2 1755-1762 p 376-379)

[iii] Thomas

Rucker had a warrant for this land (Abstracts of Northern Neck Warrants and

Surveys, 1710-1780 Vol 3 Culpeper Co VA) dated 28 October 1756 and then dated

once again 10 March 1757. The grant was

issued in the name of James Finney on 7 June 1760 (Culpeper Co VA Land

Grants). A deed from 1775 stated that

the James Finney received this land in 1757 (Culpeper Co VA Deed Book H p 164)

[iv]

(Culpeper Co Deeds Vol 2 1755-1762 p 214-216)

[v] (Orange

Co VA Will Book 2)

[vi] Other

children’s ages also guesses based upon James Finney (2) and John Finney (2)

birth dates and the order they were listed in the James Finney Sr. 1764 will

(Culpeper Co VA Will Book A 1749-1770 p 380-384)

[vii] From

the sale of remainder of James Finney land by his sons in 1785 (Culpeper Co VA

Deed Book N p 182-185)

[viii]

Description of 476 acre grant (Abstracts of VA Northern Neck Warrants and

Surveys 1710-1780 Vol 3 Culpeper Co VA) and (Culpeper Co VA Land Grants)

[ix] James

Finney (2) and John Finney (2) sold their father’s land on 3 September 1785

which included two tracts: one was the 126 acre tract and the other the 200

acre tract from 1735. This tract was

said to have the plantation situated on it (Culpeper Co VA Deed Book N p

182-185)

[x]

Inventory of James Finney will 1765 (Culpeper Co VA Will Book A 1749-1770 p

380-384)

[xi]

Inventory of James Finney will 1765 (Culpeper Co VA Will Book A 1749-1770 p

380-384)

[xii]

Inventory of James Finney will 1765 (Culpeper Co VA Will Book A 1749-1770 p

380-384)

[xiii]

Inventory of James Finney will 1765 (Culpeper Co VA Will Book A 1749-1770 p

380-384)

[xiv]

Inventory of James Finney will 1765 (Culpeper Co VA Will Book A 1749-1770 p

380-384)

[xv]

Inventory of James Finney will 1765 (Culpeper Co VA Will Book A 1749-1770 p

380-384)

[xvi]

Inventory of James Finney will 1765 (Culpeper Co VA Will Book A 1749-1770 p

380-384)

[xvii]

Inventory of James Finney will 1765 (Culpeper Co VA Will Book A 1749-1770 p

380-384)

[xviii]

Inventory of James Finney will 1765 (Culpeper Co VA Will Book A 1749-1770 p

380-384)

[xix] Inventory

of James Finney will 1765 included slaves who would need a place to live

(Culpeper Co VA Will Book A 1749-1770 p 380-384)

[xx]

Inventory of James Finney will 1765 (Culpeper Co VA Will Book A 1749-1770 p

380-384)

[xxi]

Inventory of James Finney will 1765 (Culpeper Co VA Will Book A 1749-1770 p

380-384)

[xxii]

Inventory of James Finney will 1765 (Culpeper Co VA Will Book A 1749-1770 p

380-384)

[xxiii]

Inventory of James Finney will 1765 (Culpeper Co VA Will Book A 1749-1770 p

380-384)

[xxiv]

Inventory of James Finney will 1765 (Culpeper Co VA Will Book A 1749-1770 p

380-384)

[xxv] A

guess based upon what colonists commonly grew

[xxvi]

Another guess based upon alcohol commonly made with a still by colonists

[xxvii]

Inventory of James Finney will 1765 (Culpeper Co VA Will Book A 1749-1770 p

380-384)

[xxviii]

John Finney would be hold a license to make whiskey later in Kentucky

[xxix]

Inventory of James Finney will 1765 (Culpeper Co VA Will Book A 1749-1770 p

380-384)

[xxx]

Inventory of James Finney will 1765 (Culpeper Co VA Will Book A 1749-1770 p

380-384)

[xxxi]

Inventory of James Finney will 1765 (Culpeper Co VA Will Book A 1749-1770 p

380-384)

[xxxii]

Inventory of James Finney will 1765 (Culpeper Co VA Will Book A 1749-1770 p

380-384)

[xxxiii]

Inventory of James Finney will 1765 (Culpeper Co VA Will Book A 1749-1770 p

380-384)

[xxxiv]

Inventory of James Finney will 1765 (Culpeper Co VA Will Book A 1749-1770 p

380-384)

[xxxv]

Inventory of James Finney will 1765 (Culpeper Co VA Will Book A 1749-1770 p

380-384)

[xxxvi]

Inventory of James Finney will 1765 (Culpeper Co VA Will Book A 1749-1770 p

380-384)

[xxxvii]

Inventory of James Finney will 1765 (Culpeper Co VA Will Book A 1749-1770 p

380-384)

[xxxviii]

Not sure what “turn the road at his plantation” means. It was a common request in court and may have

had to do with just creating an entrance. Maybe James Finney wanted to make a

more convenient entrance and exit to his plantation. This record is important because almost all

of the pre-Revolutionary War Court

records for Culpeper Co VA were destroyed during the Civil War. There are only a partial Court Minute Book

for the years 1763 and 1764 , which include pages 271 to 477, that survive.

[xxxix] It

seems like the order should have been the other way around. Odd that William Kirtley should object since

the Kirtley’s were known to live on the Staunton River

[xl] There

were certainly others but the Buford’s were immediate neighbors, the Quinn’s

traveled with the Finney’s to Kentucky years later, and young James Finney

married one of the Gibbs children. Sons

of John Buford who were similar aged were Abraham (b. 1749), Henry (b. 1751),

and Simeon (b. 1757). Sons of Richard

Quinn who were similar aged were Benjamin (b. 1747), James, Thomas, and

John. Sons of John Gibbs who were

similar aged were Julius (b. 1753) and Churchill (b. 1757)

[xli] The

Philip Slaughter book on Culpeper

County ( ? )

[xlii] As

earlier discussed, John Finney was born at some time around 1750, which would

have made him 12 or 13 years old. Old

enough to begin to train for his future.

This is known since in James Finney’s will, he decided that his son

James would take care of his younger son William in the event of his own

death. This decision was likely made as

John was away and since James would stay and operate the farm, he would be more

capable of providing for his brother.

Many other hints can be found later which imply that John left home and

was gone for sure in 1774. The only clue

that he may have been gone this early was the decisions made by James Finney in

his will.

[xliii]

(Culpeper Co VA Will Book A 1749-1770 p 380-384)

[xliv]

(Culpeper Co VA Will Book A 1749-1770 p 380-384)

[xlv]

(Culpeper Co VA Will Book A 1749-1770 p 380-384)

[xlvi]

(Culpeper Co VA Will Book A 1749-1770 p 393-394)

[xlvii]

There could be a book written on separating this James Finnie of Fredericksburg from James

Finney d. 1764 and James Finney d. 1819.

First of all this confusion must be solved. The Forks of Elkhorn book (Darnell, E.J.,

Forks of Elkhorn Church, Genealogical Pub Co, Baltimore 1980), which has been a

great source of information in Woodford

County , Kentucky Fredericksburg

is obviously not James Finney d. 1764 because James Finnie of Fredericksburg was alive in 1769. As discussed earlier, James Finney d. 1819

was born in 1752. James Finnie of

Fredericksburg was married to Ann Lynn by 1758 so they are certainly not the same

person. This brings into consideration

one last possibility. Could James Finnie

of Fredericksburg

actually be James Finney b. 1708, who then had a son James Finney b. about

1729, who then married Elizabeth Turner and died in 1764? If this is so then the James Finney b. 1708

would have been widowed and then remarried Ann Lynn in 1757 or 1758 (who was

previously married to John Dent before 1752) at the age of 50. This is a very sketchy scenario with some big

holes. For one, the 1735 land James

Finney b. 1708 bought in then Orange County would have to have been given to

his son, the unconfirmed James Finney b. 1729.

Second, James Finnie d. 1764 would have come to newly formed Culpeper

County at about the age of 22 as a farmer and bought more land which was pretty

rare for such a young lad. Third, the

will of James Finney sounded like the will of an older, sick gentleman, not a

young 33 year old. Fourthly, James

Finnie of Fredericksburg ’s

name was always spelled Finnie and never Finney. Lastly, there are no deeds or documents of

any kind that link these two men in any way and it is most likely that they

were of two completely different families.

[xlviii]

William Lynn’s will (Spotsylvania Co VA Will Bk B 1749-1759 p 10) and a court

summons (Spotsylvania Co VA Court Records p 350). William Lynn owned several tracts of land in Culpeper County

[xlix]

(Spotsylvania Co VA Deed Book G 1766-1771 p 252)

[l]

(Culpeper Co VA Deeds Vol 4 1765-1769 p 351-355)

[li] 16

October 1780 Culpeper County VA deeds, James and Mary Duncanson to Thomas

Porter

[lii] He

appears to have settled in Botetourt County sometime before 1774 (we know he

was there from 1. circa 1771 (number 7) and circa 1774 (number 49) Botetourt

County tithable lists, 2. He was in a Botetourt Co militia unit in 1774, 3. He

was not in Culpeper Co in 1780 militia lists, 4. He was found in several land

transactions after 1780, no land ownership is known for lands before 1780, 5.

John Finney was found listed as a Country Debtor in the Botetourt County

records along with Samuel McCLung and Colonel Andrew Lewis) (he was living near

Stephen Arnold and Jane Finney. Could

she have been his aunt, his father’s younger sister who has remained unknown?).